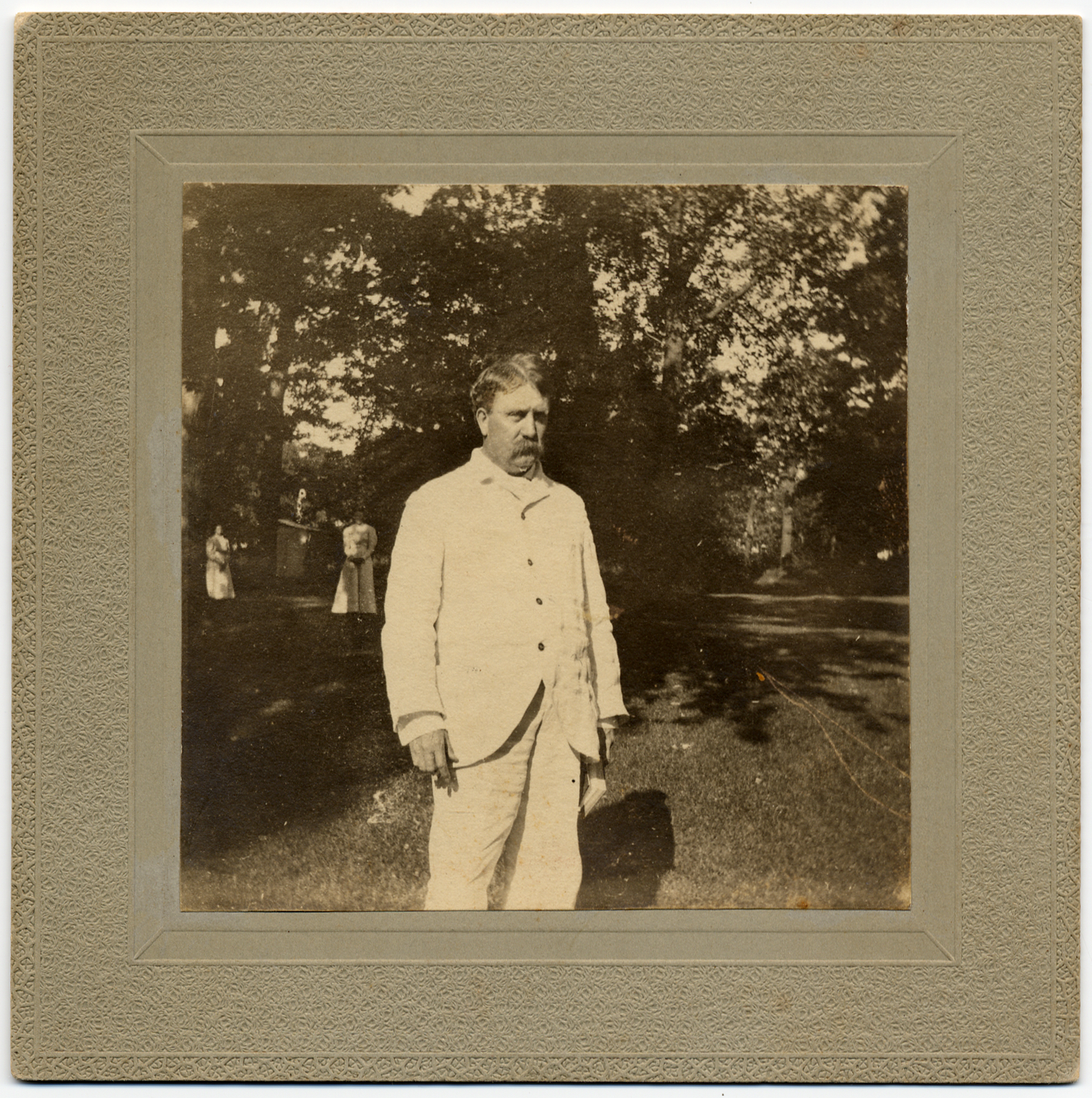

Photo: Daniel H. Burnham sketching on Dempster Beach, c.1890. Daniel H. Burnham Collection, Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, The Art Institute of Chicago. Digital file # 194301.090209-01.

Not only did Daniel Burnham call Evanston home for nearly all of his professional life, but he also left Evanston with an important architectural and planning legacy.

As the world first took note of the architect with a flair for the dramatic, whose famous line, make no little plans, characterized his boldness, it was in Evanston where the great architect Burnham found peace and quiet. It was in Evanston where Burnham was home. Home in Evanston, he wrote to his wife in 1901 while traveling in Europe, “fills my longing.”

Early Life and Life in Evanston

Daniel Hudson Burnham was born in 1846 in Henderson, New York. In 1854, his family moved to Chicago, a young town on the edge of the western frontier. As a young man, Burnham had trouble settling on a career. After failing the entrance exams at both Yale and Harvard, he worked as a salesman, traveled to Nevada to seek his fortune as a miner, and even ran for the state legislature there (and lost).

Although he had been interested in drawing since childhood and worked briefly as a draughtsman for the architect William LeBaron Jenney in 1868, it was not until 1872 that he settled on a career as an architect. After the great fire in 1871, a building boom took place in Chicago, and Burnham quickly found himself with a growing list of clients, a talented partner, John Wellborn Root (1850-1891), and an innovative architectural firm, Burnham and Root. Their work in skyscraper design became part of the revolutionary Chicago School of Architecture.

In 1876, Burnham married Margaret Sherman, the daughter of one of his clients. In 1886, the couple moved from their Michigan Avenue address to Evanston, intent on escaping the crowded city to raise their five children: Ethel, John, Hubert, Margaret, and Daniel, Jr. Burnham wrote to his mother, explaining the move: It is the only place I could go as I have come to feel and still stay in Chicago.

In Evanston, Burnham purchased an estate that encompassed two city blocks. Located at 232 Dempster Street, the Italianate style house sat on an immense piece of property bordered by Forest, Dempster, and what was then called Lincoln Place (now Burnham Place). With a sandy beach and densely wooded areas, the Burnhams Evanston property afforded the family clean air and recreation amidst the quiet atmosphere of a small town.

Burnham described the property and house to his mother this way: The place itself is handily situated on the lake shore, in the center of the town of Evanston, and is very beautiful The house is an old but very good one. There are sixteen rooms on 2 floors, some of the prettiest rooms and outlook you ever saw. There are two large lawns shaded by the great trees and a very good barn, ice house, etc.

In later years, Burnham made significant changes to the house and property, including building a tea house and tennis court, as well as a terrace wall to protect the property from lake erosion and shelter it from Sheridan Road (which was planned to follow the lake front through Burnhams property). It was noted that these changes would recall a bit of the White City that he had a hand in shaping in 1893.

Living in Evanston, the Burnhams made many connections with other prominent Evanston families, and they were active in many local organizations, including the Evanston Club. Burnham noted that Forest Avenue is becoming the choicest street in Evanston and the neighborhood is already made, and the people are first. The Burnhams hosted numerous garden parties, 4th of July celebrations and cultural events at their home. They held painting parties at the lakefront, Christmas Day open houses, picnics and baseball games on their lawn, and teas on their terrace with occasional theatrical performances. Some of the countrys most prominent artists and architects visited the Burnham home, including architect Charles McKim (who referred to the Burnham house as Camp Burnham); poet Harriet Monroe; sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudins; and landscape planner Frederick Law Olmstead.

Burnham’s Evanston neighbors also became his close professional associates. Charles Gates Dawes, who lived just a few blocks from the Burnhams, enjoyed an especially close relationship with Burnham; the two men shared an interest in civic affairs. As a member of the Commercial Club of Chicago, Dawes was a sponsor and promoter of the 1909 Plan of Chicago.

While living in Evanston, Burnham designed a number of structures in the city that still stand, including the Noyes Cultural Arts Center, Miller School, now the Chiaravalle School, Fisk Hall at Northwestern University, and the First Presbyterian Church. Emmanuel United Methodist church was designed by the firm of Burnham and Root, although it is largely attributed to Root. Many of the estate houses Burnham designed have been razed, including the Hugh Wilson house which once stood on Davis Street and Forest Avenue, and Charles Deerings home. Many of the residences he designed in Evanston were for family and friends, beginning with his sister Claras house (231 Dempster), Dr. Charles Fullers home (1305 Forest) and two homes on Dempster for William L. Brown.

Architectural and Planning Career

During these years, Burnham also took on the projects that he is known for around the world: architect of some of Americas earliest skyscrapers and Director of Construction for the 1893 Worlds Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which brought the Beaux-Arts style to Americans en masse and sparked the craze for re-designing Americas cities.

His experience in directing the creation of the White City (as the Columbian Exposition came to be called) inspired him to dedicate his remaining years to the urban planning and the City Beautiful movement. He created plans for San Francisco, Washington D.C. and Manilaprojects that culminated in his comprehensive 1909 Plan of Chicago.

Upon Burnhams death in 1912, his architectural firm was the largest in the world. Two of his sons, Hubert and Daniel, Jr., renamed the firm Burnham Brothers, and embarked on their own architectural careers, which included working on the 1933 Century of Progress Worlds Fair in Chicago. The brothers also served as key architects for Evanstons own attempt at city planning. In 1916, the Evanston Small Parks and Playgrounds Association, founded in 1909, appointed a City Plan Committee in order to create a plan for Evanston. Hubert and Daniel, Jr. served as the plans architects, along with architects Thomas E. Tallmadge and Dwight H. Perkins. A number of prominent Evanstonians funded the plan, including Margaret Burnham and Charles Gates Dawes.

Issued in 1917, the Plan of Evanston was intended as a guide for gradual development over an extended period of years. It also clearly bore the mark of Daniel Burnham and the City Beautiful movement that he had marshaled. The plan concentrated on creating park and playgrounds, improving street circulation, and encouraging the proper development of business centers in Evanston. In its call to create a grand city center and public mall, an auditorium and museum, and public parks running the full length along Evanstons lakefront, the plan mirrored Daniel Burnhams vision of the ideal American city.

In 1938 the Burnham house was demolished and the property subdivided into Burnham Park, consisting of nineteen lots with a center allee that was not to be built upon, but left open to nature. Today, all that remains of Camp Burnham is the eastern section of the concrete terrace wall, and the Tea House, which, along with later additions, is now a private home.

Many thanks to The Art Institute of Chicago, Daniel H. Burnham Collection, Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, for granting us permission to use images from their collection.